Urban AI: gardening by algorithm?

A review of Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg's new work 'Pollinator Pathmaker', a digitally-generated artwork for insects. Written with Nina Carter for It’s Freezing in LA!.

Last month, artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg opened the first planting of ‘Pollinator Pathmaker’, a new artwork for pollinators. It’s Freezing in LA! went to see this intriguing new work, and spoke to the artist about knowledge, anthropocentric art and avoiding NFTs. Words by Martha Dillon and Nina Carter, illustrations by Nina Carter. Edited by Jackson Howarth.

The green movement’s favoured planting strategies imply that we shouldn’t get too involved with ecology. Rewilding is popular: restoring and withdrawing from land to allow ecosystems to flourish and regenerate organically. So too is the idea of environmental stewardship and living as part of ecosystems, a similarly non-invasive approach that is often linked to concepts described by some Indigenous Peoples. Guerrilla Gardeners and De-pavers, who don’t share a uniform approach to horticulture, embrace the idea of pushing back human-made urban spaces to allow ecological systems back in by any means.

These attitudes all suggest that plants are more complex and mysterious than we can fully conceive of. And indeed, Western monocultures, manicured lawns and obsessive categorisation of species have created catastrophic loss of ecological life and contributed to an emissions crisis that we must quickly reverse. While we can eliminate carbon emissions relatively rapidly, a garden or forest can take hundreds of years to fully take root. Growing is unfashionably, painstakingly, mystically slow compared to the urgent timescales of climate action.

Growing is unfashionably, painstakingly, mystically slow compared to the urgent timescales of climate action

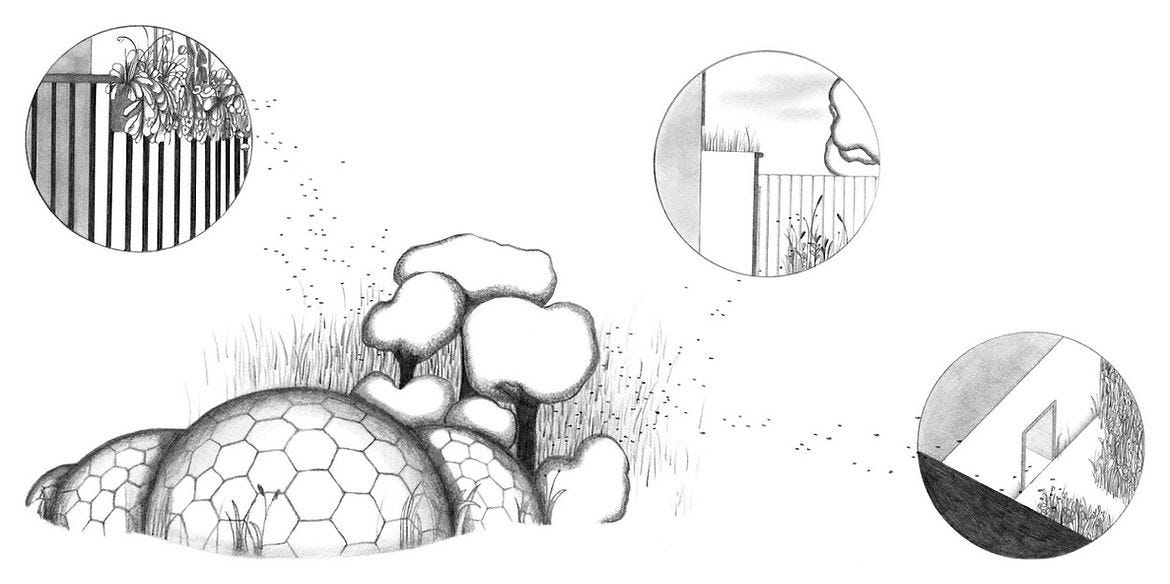

The slow emergence of ecosystems was partly why visiting Pollinator Pathmaker, a new project by artist Alexandra Daisy Ginsberg, was a strange experience. The garden sits on the slopes of the Eden Project, a Cornish china clay pit that was rehabilitated into a network of gardens and biomes in 2000. Planted just last year, the Pollinator Pathmaker plants are only just beginning to peek through: tufts of spiky grasses criss-cross a 55m long walkway, interspersed with 64 species of just-flowering friends, such as ‘the towering Echium pininana loved by moths, solitary bees, bumblebees, honeybees, and butterflies, the Cornish heath Erica vagans which attracts bumblebees, flies, hoverflies, butterflies, and moths, and Aquilegia vulgaris, a favourite for short and long-tongued bumblebees.’ There’s still some bare earth, and currently fewer pollinators than in the longer-established, noisy gardens further on – ‘there's never an optimal [time]’ Ginsberg tells us, when we ask her when we should see the space. ‘Different flowers bloom over the year, although the fewest flowers will be in winter when the fewest pollinators are around. If you come in spring, the flowers and insects will be different to autumn. But we have to wait for the garden to grow in its own time’.

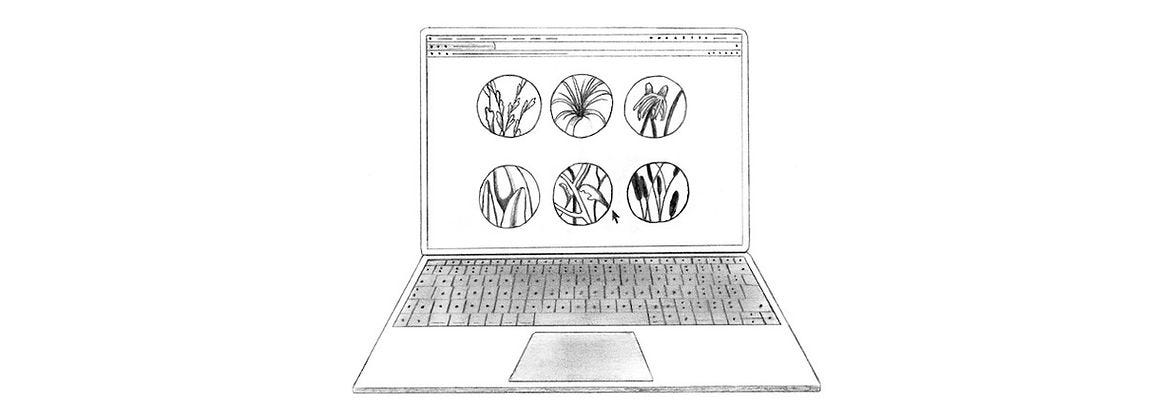

But Pollinator Pathmaker is an artwork, and it isn’t just this one garden. Ginsberg, with string theory physicist Dr Przemek Witaszczyk, has created an “empathy” algorithm that intends to calculate the layout and combination of plants that will support as many pollinator species as possible, using plants appropriate for the location. The algorithm balances different pollinator species and foraging strategies considering local conditions, such as soil type; and user’s design choices, such as ‘pattern intricacy’. The Eden Project, who commissioned the work, has planted the first iteration, with plots underway at London’s Serpentine Gallery and Light Art Space (LAS) in Berlin. An online version at pollinator.art allows all of us to ‘use the artwork’s custom algorithm to generate our own unique planting scheme of locally-appropriate plants for bees and other pollinators.’

The artwork provokes us to hand over planting responsibilities to an algorithm in a manner that, at first glance, feels deeply antagonistic to the rewilding and stewardship models. It proposes distilling the mysteries of plants into a faceless, human-written, speedy algorithm. It suggests that it might be possible to write down what an ecosystem ‘needs’ in a simple piece of code. ‘When you start to play with [technology and biology],’ Ginsberg has said previously of her exploration of the field of synthetic biology, ‘you start to understand what questions we need to ask about it, what about it should worry us.’ The same applies today, she says: ‘I play with technology in my work as a way of thinking about why we prioritise technology over preservation or looking after the natural world. Why has modern humanity favoured innovation over preservation?’

Pollinator Pathmaker makes us think about knowledge mechanisms. All gardens, meaning ecosystems initiated and maintained by humans, store knowledge; in the positioning of plants, their behaviours and features. Their care is passed across and along cultures in a much-loved mixture of oral, visual and written traditions. The Pollinator Pathmaker algorithm is designed to take ‘palettes’ of inputs based on local knowledge about species, pollinators behaviours and environmental conditions. Ginsberg worked closely with ‘Eden’s horticulturalists, external pollinator experts and scientists, and published research and guides’ to create the first plant palette, which is considered appropriate for Atlantic Europe. The work is asking whether you might be able to code real experience into the algorithm; whether there could be a new vehicle for storing, channelling and sharing gardening knowledge. You can tangibly sense this flow of information as you walk through the Eden Garden’s Pollinator Pathmaker: the garden has been planted based on learnings from the wider site, and its busy pollinators will go on to stimulate more growth across it and beyond – a different approach to the manicured, closed biomes of carefully curated plant species that made the Eden Project famous.

The work also questions who gardens are for. ‘Pollinator Pathmaker is a campaign to make art for pollinators, planted and cared for by humans’, says the website. ‘We want to transform how we see gardens and who we make them for.’ ‘We care about the environment of the world because we want it to be liveable for us’ explains Ginsberg. ‘[But] that's a very anthropocentric way of looking at it. There are many other moral and ethical arguments for not destroying our environment, aside from human survival. How can we see the world we create and destroy from the perspective of the other species that we share it with?’

In practice, the work is more subtle, with the algorithm espousing a blend of pollinator and human preferences: ‘the intention is to use the technology to buffer ourselves from the ordinary choices we make when we make gardens. Can we ever design for other species, rather than for ourselves?’, asks Ginsberg. The tool allows you to choose the number of species you’ll use, influence the patterns the species will make, and of course define the characteristics of the space itself. Whether the project connects or disconnects us from the ecological system becomes unclear; are we designer, student or caretaker? We can’t help but insert our will into the process. ‘These are unnatural gardens, designed for nature,’ she explains. This discomfort is characteristic of Ginsberg’s work, which has always sought to explore our ‘fraught’ relationship with biology – she has previously resurrected the smell of extinct flowers, rebuilt the dawn chorus using machine learning, and created a simulation of wilding the planet Mars over one million years.

‘These are unnatural gardens, designed for nature’

Ginsberg experiments with advanced and emerging technologies in all these projects: AI, genetic engineering and simulations. In Pollinator Pathmaker, the algorithm and website interface are slick, quick and gamified. They capture our attention and senses; the technology is harnessed to pull us into experiences. But this work is the most direct she’s been in inviting the viewer to participate actively. We are not just asked to smell, hear or imagine a garden created by an algorithm, but actually to plant one. ‘It’s anti-NFT’, she explains, which are ‘about scarcity value, [being] non-fungible… mine is fungible. Yes, it’s location specific, but it’s unlimited. And the more gardens the better, because the more editions near each other, the more they’ll all thrive.’ The viewer is invited to put in physical time and effort to plant a garden.

The fact that we are asked to actually plant a garden is also the most challenging part of the project. What if this is a problematic way to live among ecosystems?

Putting the core idea of planting with algorithms to one side, Eden’s horticulturalists’ and other pollinator experts' knowledge are currently the main source of experience being applied in the algorithm. But ecosystems are precisely calibrated to their location and conditions – a lovingly rehabilitated Cornish china clay mine biome and a small urban garden somewhere else are different creatures. The current artwork isn’t yet circulating knowledge, it is pollinating a simplified model based on knowledge from the original location. Ginsberg is considering what a more complex algorithm might look like: new ‘palettes’ of inputs are being created for different locations, such as Germany, for the LAS garden. And what if the algorithm was a learning one, taking in the results of the planted gardeners and becoming more complex, a genuine conduit for knowledge? ‘It's not a machine learning algorithm’, says Ginsberg. ‘But, in theory… the 2.0 could be more “intelligent”.’

Ecosystems are precisely calibrated to their location and conditions – a lovingly rehabilitated Cornish china clay mine biome and a small urban garden somewhere else are different creatures

It feels possible that Ginsberg's provocations will be misunderstood. Indisputably, viewers are exhorted to build these gardens – it's explicitly described as a ‘campaign’ and a ‘call to action’. We are provided detailed planting instructions, and the campaign has major sponsors, like Google Arts & Culture. Yet, Ginsberg is clear that Pollinator Pathmaker is an experiment: ‘it's not a solution. This is not going to solve the pollinator crisis in any way… what I want to happen is to be asking people to think about what art is, what it's for, how can art transform us?’ Ginsberg suggests that ‘we’re changed from consumers into caretakers.’

Ultimately, any consequences are unlikely to be extreme – novice gardeners may be inspired to create much more biodiverse gardens than they might otherwise, and learn a huge amount in doing so. But the work is an excellent reminder that we should be approaching environmental campaigns and projects with healthy scepticism. A campaign involving trees and good marketing does not automatically equal good environmental credentials.

Ginsberg’s work is affecting. It tests truths from different sides: the idea that an algorithm could compete with the natural world, if we are comfortable with how long climate restoration will take, and whether we should blindly follow climate campaigns. It asks questions of popular arguments about being less interventionist with ecosystems; as such its mission to involve the viewer feels challenging. But, just as there is no ‘best’ time to look at a garden, perhaps we need to reign in our urgent climate activist instincts and let it grow.

Pollinator Pathmaker was originally commissioned by the Eden Project funded by the Garfield Foundation as part of Create a Buzz. Additional funding supporters Gaia Art Foundation and collaborators Google Arts & Culture. See the gardens in London and Cornwall this summer and soon in Germany. More info - https://pollinator.art