Carbon Accounting Myths II - national targets

How does carbon accounting work at global scale, and why does it fail countries in the Global South? For It’s Freezing in LA!.

You can order a print or digital illustrated copy of this article in It’s Freezing in LA!, where it was originally published.

In November 2021, the COP26 climate conference hopes to ‘finalise the rulebook’ on the Paris Agreement, the major 2015 international accord under which states have been setting targets for reducing their carbon emissions. Martha Dillon takes a look at the success of the approach so far. She finds a system that is struggling to meet its own goals, with gross inequities being inked into international climate agreements. Edited by Grace Richardson Banks and illustrated by Rebecca Danning.

Illustration by Rebecca Danning. (C) It’s Freezing in LA!, 2022. Reproduce with credit only.

‘I was born in India’ says COP26 President and UK Conservative MP Alok Sharma, ‘I have real sympathy with less developed countries that feel it’s for the developed industrial nations to help sort out a problem largely of their making.’ As the curtains rise on COP26, the annual international conference at which states negotiate their climate responsibilities, the pressure is on for Sharma and his team to convince industrial nations to make more ambitious climate targets. But what are these targets trying to achieve, and are they doing enough?

A Carbon Accounting Deadlock

The current system is simple and ineffective: COP negotiations manage the terms of the Paris Agreement, under which states come up with individual targets for decarbonising (‘NDCs’). These targets represent the amount of action they are willing to undertake to contribute to the Paris Agreement 2oC goal. There is no specific calculation by which these targets have been set, and no requirement that states comply with any particular result. At the time of writing, China, the US and India are the world’s biggest emitters, and have committed to 65%, 50% and 35% cuts to 2005 emissions levels by 2030, respectively. As Nathan Thanki (co-coordinator of the Global Campaign to Demand Climate Justice) describes, the process of agreeing NDCs has been ‘very much just people stabbing in the dark... consultant-driven, not based on the best available science, not based on equity.’ This bottom-up approach might avoid negotiation deadlocks, but this is at the cost of actual results. The combined set of current NDCs are projected to leave us 80% wide of meeting the 2°C target: To put it another way, even if all countries meet their current NDCs, there is only a 26% chance that the planet will stay below 2°C of warming.(1)

The free-for-all architecture of the Paris Agreement has failed to produce a pathway to avoiding catastrophic climate warming. But it is not just current targets that are insufficient; there has been some very creative carbon accounting. Under the NDC system, countries typically only report the burning of fossil fuels inside their geographical boundary – ‘territorial emissions’ – excluding the ‘consumption emissions’ of imported goods. To take the example of the UK, who are hosting COP26 in November, emissions from the carbon-intensive process of producing aluminium in China won’t factor into the UK’s NDC, no matter how much of it is imported to build British skyscrapers. In 2016, the UK proudly reported territorial emissions of 473 millions of tonnes of CO2e, a seemingly impressive 41% reduction from 1990 levels. In reality, the true UK carbon footprint nearly doubles when imported goods are included, making the true figure 801 MtCOte in 2016, only a 15% reduction from 1990 levels.(2)

Caption: UK emissions from territorial, production and consumption in 2016 (MtCO2e). Source: WWF, 2020.

The use of territorial emissions reporting enables states to avoid responsibility for carbon-intensive – not to mention environmentally and socially destructive – industrial activities overseas. The prime culprits are wealthy western nations, like the UK, that remain dependent on the continued colonial exploitation of cheap labour and goods abroad.

This is one of the many ways in which the current COP carbon accounting and target systems reflect familiar patterns of global governance, riddled with ingrained power imbalances, extractive ideologies and colonial relationships that characterise the state of border relations worldwide. ‘Most people in most organisations setting targets on behalf of organisations are acting in good faith’ says prominent built environment campaigner Maria Smith. ‘But most people aren't really questioning the frameworks we report within. These systems aren't objective, they entrench ideologies, and the more commitments and pledges we make against a flawed system, the more lock-in there'll be.’

A New Approach

The problem of territorial and consumption emissions is one of many issues with attempting to draw neat lines through the patchwork of carbon emissions influenced by many different groups. But while carbon accounting and target setting remain the language of international agreements, there are ways to move away from these problems.

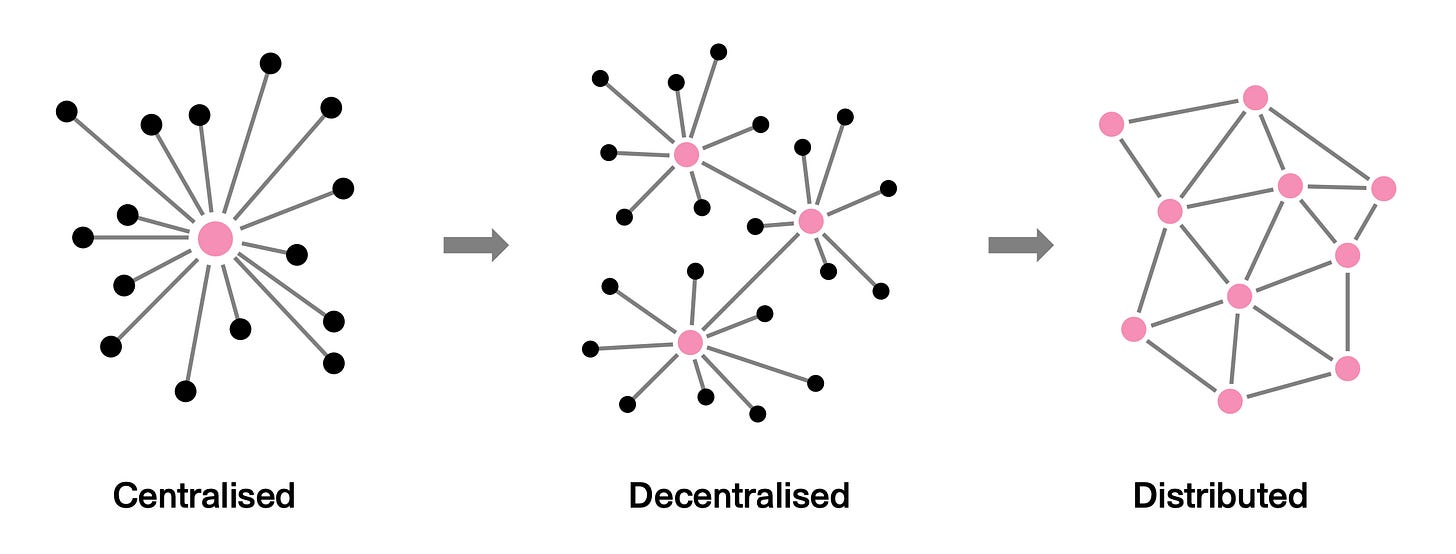

Notably, a distributed system of carbon accounting, in which states and companies take a full, shared responsibility for their carbon emitting activities, is much more coherent. Not only will it prevent activities falling through the cracks, it requires mutual and collective approaches to decarbonising, with buy-in from influential groups. This is a step away from pointless attempts to divvy up responsibility for emissions along boundaries that are skewed in favour of powerful and wealthy groups and nations. Requiring the UK to take responsibility for consumption emissions outside its geographical boundaries would constitute a distributive system. It would force the UK to support the development of safe alternatives to high-carbon, destructive overseas manufacturing processes that UK residents rely on for imported goods, prioritise carbon negotiations in trade agreements and regulate government spending abroad – closing loopholes that enable UK state financing of overseas fossil fuel projects, for example.

Caption: a distributed system of climate actors working toward common emission reduction goals. Source: SBTi, 2018.

States must also set targets at a level of ambition relative to their influence and wealth. There are already methodologies available to do this calculation: Thanki’s work has drawn on the Civil Society Review’s Climate Equity Reference Calculator,(4) an approach that calculates national targets based on factors like responsibility, capability and population income distributions. By their calculation, the UK would need to cut 1990 territorial emissions by around 200% within the next decade to take on its ‘fair share’ of the global effort to limit climate change – again, this means initiating decarbonisation within and outside the UK.(5) Organisations like the African Group, Like-Minded Developing Countries and a number of governments from the Global South have proposed ‘conflict of interest frameworks’ that could complement equity calculations, forcing companies and states whose profit-making depends on harming the climate to declare these interests in arenas like COP. This would mean the US admitting responsibility for companies like the Chevron Corporation, which was the second largest industrial greenhouse gas emitter in the world between 1965 and 2017, taking about half its earnings internationally (in 2017). Under the current Paris Agreement system, the US only accounts for Chevron products burnt within the USA, let alone acknowledging Chevron’s considerable lobbying efforts and purchasing power.

Ultimately, target setting systems would benefit from moving away from carbon as a metric for climate action entirely. As Thanki explains, ‘our society's approach to dealing with ecological crises has been to basically double down on what we know... [assuming that] because you measure it, that's what makes it real.’ In other words: we are obsessed with financialising and metricising complex problems, even when, at a basic level, a tonne of carbon is not a very accurate unit on which to hang the solutions of a crisis that crosses every aspect of society, the economy and the environment. A truly effective mitigation system would focus on outcomes and policies that enable communities and ecosystems to flourish and explicitly prohibit damaging activities, rather than remaining hung up on trading, accounting and mitigating.

Breaking the Deadlock

It’s free-for-all origins got the Paris Agreement off the ground, easing early negotiation deadlocks when climate action was less high on domestic agendas. But carbon accounting reform is no immediate fix to the climate crisis, and no substitute for fossil fuels staying in the ground. Thanki and Smith are both clear that targets in the Paris Agreement may be useful for campaigners to point at, but are ultimately reflections of prevailing ideology.

But today, we can ask for more. Target setting and carbon accounting systems create big-hitting headlines, define the basic terms under which groups acknowledge their climate responsibilities, and have proven a core metric for climate action in the popular consciousness. Leveraging this progress and standardising the rules could hold groups accountable for the full breadth of their activities, and ask for more from the influential and powerful. It would be a profound and focussed step towards a more equitable, shared, cross-border mindset in climate action.

At COP26, there are no grand plans to redesign the core architecture of the Paris Agreement. Sharma wants to push richer industrial states to support global decarbonisation yet also wishes to ‘finalise the Paris Rulebook’ – a rulebook that currently allows these same states to disavow their considerable footprints and influence abroad. ‘This COP can't just be about tightening the screws on the existing decarbonisation machine’ says Smith. ‘It also needs to be about questioning the operation and configuration of all the parts of our international climate action and creating commitments and pledges that entrench equity.’ Finalising the rulebook would be disastrous.

Footnotes:

Peiran Liu and Adrian Raftery, Country-based rate of emissions reductions should increase by 80% beyond nationally determined contributions to meet the 2 °C target, 2021

WWF, Carbon Footprint: Exploring the UK’s Contribution to Climate Change, 2020

Daisy Dunne, Unacceptable loopholes’ could undermine UK pledge to end overseas, fossil fuel funding, campaigners say, 2021

Climate Equity Reference Calculator, 2021

Climate Fair Share, Technical Document, 2020